Archishman Sarker Speaks at the CSMC’s Workshop on ‘Written Artefacts’ at the University of Hamburg

Archishman Sarker shares highlights from his talk at the CSMC workshop, his research on Buddhist manuscripts, and the engaging discussions at the event.

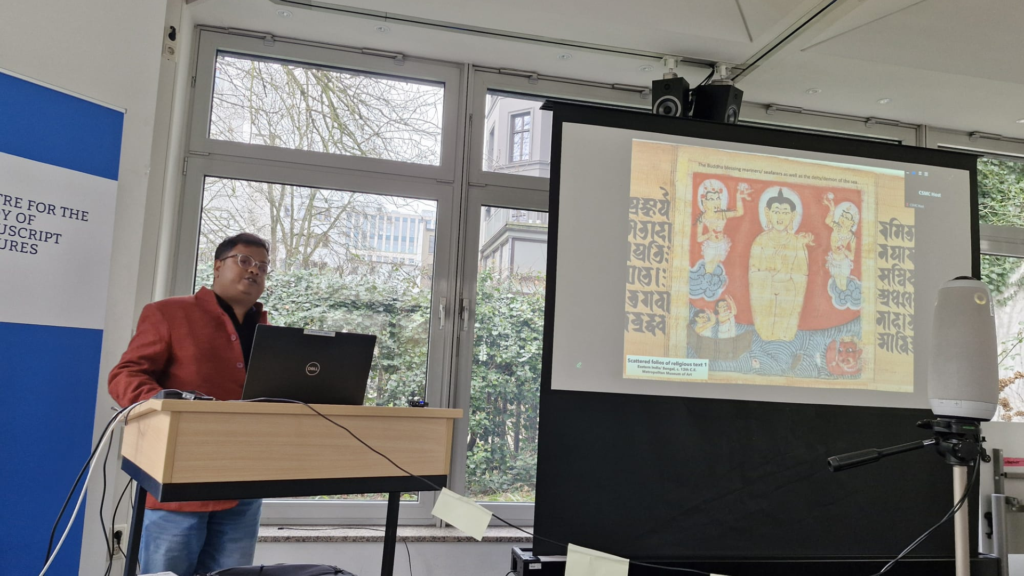

Archishman Sarker, art historian and Senior Writing Tutor, Centre for Writing and Communication (CWC), Ashoka University, was recently invited to deliver a talk at the prestigious Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures (CSMC), University of Hamburg, as part of their workshop on ‘Social Time in Written Artefacts’.

In this interview, Archishman shares his experience at the workshop, the significance of his research on Buddhist manuscripts, and the engaging discussions that took place during the workshop. He also shares insights into the evolving study of manuscript cultures and offers advice for scholars interested in this field.

Congratulations on being invited to deliver a talk at the workshop conducted by the Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures (CSMC), University of Hamburg. Could you tell us a bit about the experience as a whole and how this opportunity came about?

The Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures (CSMC) at the University of Hamburg is among the foremost institutions globally for the scientific study of manuscripts. For over five decades, the centre has played a pivotal role in the preservation, conservation, and digitisation of Indian manuscripts in Nepal, particularly through initiatives such as the Nepal-German Manuscript Preservation Project (NGMPP) and the Nepal-German Manuscript Cataloguing Project (NGMCP). Given that my recently submitted doctoral dissertation at Jawaharlal Nehru University examines medieval Buddhist illuminated manuscripts from eastern India – many of which have been digitised under these projects – visiting the CSMC was a profoundly significant experience for me.

The experience overall was very inspiring and I of course learnt a lot, not just from the other participants at the workshop from universities around the world, but also from the infrastructure and expertise at the centre itself, for example, their spectroscopy equipment for studying manuscripts whose functioning we came to understand through a visit to the different world-class laboratories at the centre, staffed by the best people in the field. I was invited to this workshop in November. I was probably chosen for it because of my long-standing engagement in the field, and my recently completed Ph.D. on the subject.

Could you elaborate a bit on your talk at the ‘Workshop: Social Time in Written Artefacts’, particularly the topic you addressed – ‘Social Time’, ‘Linearity’, and the Materiality of Memory?

My talk focused on the enduring influence of colonial historiography on the study of medieval Buddhist manuscripts from eastern India and Nepal, arguing that its linear and synchronic frameworks have not only shaped but also constrained contemporary understandings of these textual traditions. Focusing on the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitāsūtra manuscripts, the analysis examined their reception, dissemination, and preservation through the lens of ‘social time.’ Special attention is given to their role within contemporary urban Nepal, particularly among Buddhist communities in the Kathmandu valley and the Hiraṇyavarṇa Mahāvihāra in Kwa Baha, Patan (Lalitpur).

I contended that colonial influence on modern historiographical models obscure the intricate processes of cultural association, dissociation, and appropriation that have historically shaped Himalayan manuscript cultures, where manuscripts often play the role of ‘living agents’ in the construction of ‘social time’; thus situating these manuscripts within the localised and interconnected contexts of Buddhist communities in Nepal and adjacent Himalayan regions – where manuscripts produced in eastern India during the Pāla dynasty (eighth to twelfth century), were actively translated, preserved, and disseminated.

Were there any interesting discussions or perspectives shared during the workshop that stood out to you?

There were indeed numerous instances of intellectually stimulating exchanges throughout the workshop. For example, a colleague from the Asia-Africa Institute in Hamburg, Nelson, presented a compelling study on King Aśoka’s distribution of relics within the Chinese Buddhist landscape. This perspective offered valuable insights into the transmission and reception of Indian Buddhism in China.

Similarly, Johanna, a colleague from Princeton, examined archaeological preservation in the coastal Indian state of Gujarat, with a specific focus on the region of Diu. Her paper explored the role of Diu in early modern maritime networks and engaged with a range of historical materials, including Portuguese sources, which provided a fascinating lens on trans-regional interactions. Additionally, two scholars from the Free University of Berlin discussed the construction of “social time” from a Latin American perspective, employing cartographic hermeneutics as an analytical framework. Their approach was particularly thought-provoking in its engagement with conceptual historiography.

Beyond the individual presentations, the workshop was structured to facilitate extensive discussions and debates. As all participants were early-career researchers working on various aspects of “social time,” this format proved to be highly productive.

Towards the end of the workshop, we formed smaller working groups to develop a prospective publication based on our collective discussions. This collaborative effort will continue in the coming weeks and months, with the goal of finalising the publication by the end of the year.

What advice would you give to other students or researchers interested in the study of written artefacts or in participating in similar workshops?

For students and researchers interested in the study of written artefacts, I would emphasise the importance of developing a strong foundation in both historical and material analysis. Engaging with primary sources firsthand, whether through archival research or manuscript studies, is invaluable. At the same time, familiarity with emerging scientific methodologies – such as spectroscopy, multispectral imaging, and codicology – can significantly enhance one’s approach to the materiality of texts.

For those looking to participate in workshops of this nature, I would recommend being proactive in seeking interdisciplinary and trans-disciplinary dialogues. The most enriching discussions often occur at the margins of disciplines, where diverse methodologies and perspectives converge.

It is also crucial to approach such opportunities with a willingness to both contribute and absorb – collaborative intellectual environments thrive on reciprocity. Finally, cultivating a network of scholars working on related themes can open doors to further research collaborations and institutional support, which are essential for long-term academic growth.

Study at Ashoka