How restaurants can help protect India’s endangered species

Divya Karnad, Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies, conducts research on shark and ray meat consumption in coastal Indian restaurants, revealing the urgent need to shift to alternatives to prevent the extinction of small-bodied species. Urgent policy interventions are essential to tackle overfishing and ensure long-term sustainability

Elasmobranchs are a group of cartilaginous fish, encompassing all species of sharks and rays. Over one third of elasmobranchs are at a risk of global extinction. The northern Indian Ocean particularly require urgent elasmobranch conservation efforts due to high fishing pressure, largely fueled by demands from the East Asian market for shark fins. To address this, India has imposed a ban on live-finning (the cutting of fins from live sharks) as well as a ban on exporting fins. Furthermore, some species in India are completely protected from fishing or trade. However, India remains the world’s third-largest exploiter of elasmobranchs and this is mainly because their meat is used for human consumption.

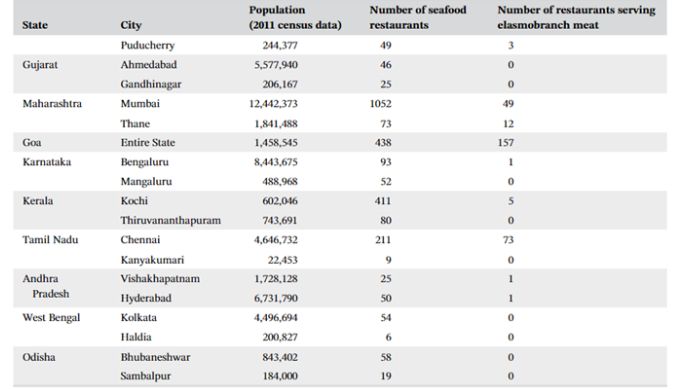

Research led by Prof. Divya Karnad at the Department of Environmental Studies, Ashoka University, has now advanced our understanding of elasmobranch meat consumption in India and suggests ways to transition to alternatives. Prof. Karnad’s research team identified the hotspots of shark meat consumption in India, with a particular focus on coastal states. Within each of the ten states, they selected cities with large populations and a culture of seafood consumption. They categorised restaurants serving elasmobranch dishes in each city based on their price range and cuisine, and thoroughly examined them.

Restaurants in cities across 10 coastal states (including Puducherry, a Union Territory) serving seafood and elasmobranch meat

Through interviews, it was discovered that Goa had the highest proportion of restaurants selling elasmobranch meat, followed by Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra. Interestingly, elasmobranch meat was predominantly sold in restaurants offering regional cuisine, as it was regarded as the symbol of traditional coastal dishes, appealing to customers seeking authentic flavours.

The study revealed that various shark species are being sold as “baby shark”, including smaller species such as milk shark, and others. The demand for small-bodied species and juvenile sharks leaves them particularly vulnerable to this trade. This threat to the juveniles is particularly alarming, as it could lead to the decline of large-bodied species. Hence, targeted conservation efforts or regulations focused on restaurants in these hotspots could potentially yield benefits. One such measure could involve removing shark meat from restaurant menus.

However, this approach faces challenges. In Goa, for instance, most of the restaurants rated shark meat as among their more popular dishes, both in terms of profitability and customer demand. Some respondents also expressed concerns that substituting shark meat would result in a notable negative effect on profits. Particularly, restaurants located in high tourist zones acknowledged the potential financial consequences of removing sharks from their menus, and anticipated a significant impact on their business.

Nevertheless, the study also revealed that the majority of the restaurants believe that excluding elasmobranchs from their menus would not have a significant impact on their profits. Additionally, about one-third of the participants expressed openness to alternatives, such as Spanish mackerels (Scomberomorus spp.), Snappers (Lutjanus spp.), and Sea catfish (Ariidae).

The study also revealed that restaurant owners were unaware of the health risks associated with shark meat, particularly its high levels of metal toxicity. Raising awareness among restaurants and consumers about these health hazards associated with consuming sharks could potentially lead to voluntary changes in consumer consumption patterns.

Furthermore, the study suggests that policy interventions should focus not only on shark conservation specifically, but also on enhancing the overall health of marine fisheries. Ongoing research by Prof. Karnad and her team explores the role of local markets and household consumption on fueling the trade in shark meat. Policy makers need to step in to implement specific measures to reduce the affordability and accessibility of elasmobranch meat in restaurants. Further research is also essential to address crucial gaps in understanding elasmobranch fishing drivers.

Written by Kangna Verma (M.Sc. Biology, 2024) and Edited by Yukti Arora (Senior Manager, RDO, Ashoka University)

Reference Article:

Regional hotspots and drivers of shark meat consumption in India. Conservation Science and Practice, 2024; 6: e1306

doi.org/10.1111/csp2.13069

Authors:

Divya Karnad, S. Narayani, Shruthi Kottillil, Sudha Kottillil, Trisha Gupta, Alissa Barnes, Andrew Dias, Y. Chaitanya Krishna

Study at Ashoka